Vietnam War Photos by legendary photojournalists Eddie Adams, Hubert Van Es and Malcolm Browne.

We revisit the locations of these era-defining pictures.

The ‘Vietnam War’ has a special grip on the American psyche. Fifty years later, it still haunts discussion of every conflict the USA enters, serves as a badge of honour (or disgrace) for politicians, and its imagery and themes continue to pervade popular culture.

Over here in Vietnam, however, there’s only very rare talk of ‘The American War’, at least in public. People tend to want to patch up the past and move on, both for personal and political reasons. In the mass media, there’s none of the guts, inglory and guitar rock of movies like Platoon, Apocalypse Now and Full Metal Jacket. Even major novels written by Vietnamese about the conflict, like Bao Ninh’s The Sorrow of War, enjoy more renown abroad than at home.

This reticence about the war reveals itself in odd ways. Ho Chi Minh City has the interesting War Remnants Museum, but Hanoi’s counterparts are neglected and dust-devilled, and haphazardly mix exhibits from both the French and American conflicts. Meanwhile, tucked into a network of alleyways behind the little-visited B52 museum lies the wreckage of an actual B52, lodged in a pond surrounded by quiet middle class residences. You could easily walk past thinking the lichen-covered wheel strut and fuselage were the result of neighbourhood fly-tipping.

Likewise, the locations of some of the war’s most iconic photographs merit barely a small plaque, even in central Ho Chi Minh City. We visited the spots where legendary photojournalists Eddie Adams, Hubert Van Es and Malcolm Browne took era-defining pictures, and captured the scene as it appears today.

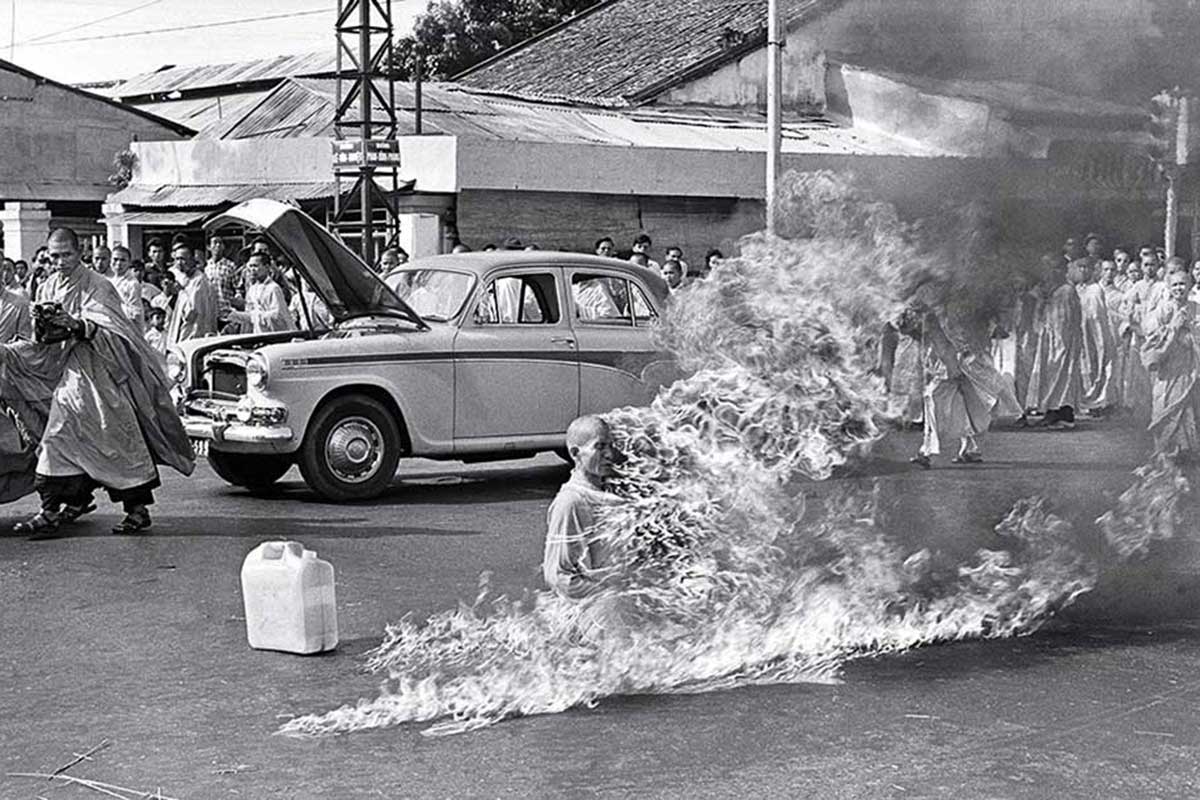

Malcolm Browne - Burning Monk

John F Kennedy said, “No news picture in history has generated so much emotion around the world.” The photograph proved a turning point in the demise of the US-backed Diệm government in Saigon, eventually bringing American troops to Vietnam.

Đức set fire to himself in protest against religious discrimination and persecution, writing in a letter prior to the act, ‘Before closing my eyes and moving towards the vision of the Buddha, I respectfully plead to President Ngô Đình Diệm to take a mind of compassion towards the people of the nation and implement religious equality to maintain the strength of the homeland eternally.’

David Halberstam, a journalist accompanying Browne, described the event graphically: ‘Flames were coming from a human being; his body was slowly withering and shriveling up, his head blackening and charring. In the air was the smell of burning human flesh; human beings burn surprisingly quickly. Behind me I could hear the sobbing of the Vietnamese who were now gathering. I was too shocked to cry, too confused to take notes or ask questions, too bewildered to even think … As he burned he never moved a muscle, never uttered a sound, his outward composure in sharp contrast to the wailing people around him.’

Browne for his part was phlegmatic: ‘I was thinking only about the fact it was a self-illuminated subject that required an exposure of about, oh say, f10 or whatever it was, I don’t really remember. I was using a cheap Japanese camera, by the name of Petri. I was very familiar with it, but I wanted to make sure that I not only got the settings right on the camera each time and focused it properly, but that also I was reloading fast enough to keep up with action. I took about ten rolls of film because I was shooting constantly.’

Browne won the World Press Photo of the Year award and the Pulitzer Prize for his picture.

Eddie Adams - Saigon Execution (1967)

Writing in Time magazine in 1998, photojournalist Eddie Adams reflected, ‘Two people died in that photograph: the recipient of the bullet and General Nguyễn Ngọc Loan. The general killed the Viet Cong; I killed the general with my camera. Still photographs are the most powerful weapons in the world. People believe them; but photographs do lie, even without manipulation. They are only half-truths. … What the photograph didn’t say was, ‘What would you do if you were the general at that time and place on that hot day, and you caught the so-called bad guy after he blew away one, two or three American people?’….

This picture really messed up his life. He never blamed me. He told me if I hadn’t taken the picture, someone else would have, but I’ve felt bad for him and his family for a long time. … I sent flowers when I heard that he had died and wrote, “I’m sorry. There are tears in my eyes.’

Eddie Adams – Saigon Execution (1967)

Adams’ picture, taken during the opening days of the Tet Offensive, won the Pulitzer Prize and a World Press Photo award. Loan fled Vietnam during the Fall of Saigon, and Adams testified on his behalf to persuade the US Immigration and Nationalization Services to allow him to stay in America. The photograph has since become a touchstone for discussions of ethics in photography. To what extent should photographers involve themselves in a situation, and what do they have the right to photograph? Susan Sontag even accused Adams and other journalists of inadvertently causing the execution, saying that the general would never have carried it out ‘had the press not been available to witness it.’

The exact spot where Adams captured the picture takes some finding: not a single sign or memorial plaque marks the place. A small furniture shop stands at the address, and traffic honks blithely up and down the road where Loan and his soldiers once frog-marched the defiant Viet Cong captain, Nguyễn Văn Lém, to his death.

Hubert Van Es - US Evacuation, Saigon (1975)

‘Around 2:30 in the afternoon, while I was working in the darkroom, I suddenly heard Bert Okuley shout, “van Es, get out here, there’s a chopper on that roof!” I grabbed my camera and the longest lens left in the office – it was only 300 millimeters, but it would have to do – and dashed to the balcony.

Looking at the Pittman Apartments, I could see 20 or 30 people on the roof, climbing the ladder to an Air America Huey helicopter. At the top of the ladder stood an American in civilian clothes, pulling people up and shoving them inside. Of course, there was no possibility that all the people on the roof could get into the helicopter, and it took off with 12 or 14 on board. (The recommended maximum for that model was eight.) Those left on the roof waited for hours, hoping for more helicopters to arrive. To no avail. The enemy was closing in.

I remember looking up to the sky and giving a short prayer. After shooting about 10 frames, I went back to the darkroom to process the film and get a print ready for the regular 5 p.m. transmission to Tokyo from Saigon’s telegraph office.’

Van Es returned to Vietnam in 1990, and commented, ‘It [Vietnam] hasn’t really changed since I was last here; but our photos changed the views of those who were lucky enough not to witness this terrible war.’

If he could see the country in 2020, for sure Van Es would be startled by the transformation; but these quiet corners that once witnessed the horrors of the ‘American War’ remain – real-life testaments to iconic images.